We are delighted to announce that work based on staff-student co-creation between Dr Elvira Bolat and Claudia Wilkin is now a basis of new article published in the Leadership journal. Paper titled ‘Mirror, mirror on the wall: Shifting leader–follower power dynamics in a social media context’ reveals complexities and power dynamics in the social media influencers-followers relationships. It is clear that there is a third wheel – social media platforms – that have power to manipulate the relationships … so we can after all blame social media giants in creating a fake news world we all live in ….

Digital ME BU Next Chapter

Digital Me BU Photo Exhibit poster (design buy Little Women)

Our next chapter with title “Digital ME BU Photo Exhibition” will be organised by Event Management students. It is free entrance for everyone.

Let come, enjoy and learn more about BU research into DIGITAL.

Location: K103- Kimmeridge House, Talbot Campus, Bournemouth University. Time: 2:00 pm – 4:00 pm. Date: 29th March 2019

More information: https://www.facebook.com/photoexhibition.digitalmebu/

RAISA* on the Public-Sector Express

An exploratory study of the resources and capabilities needed for the Public Sector to successfully adopt and utilise RAISA*.

*(Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, and Service Automation)

Background

Robotic surgeons, self-driving cars, neuro-technological brain enhancements, genetic editing, multimodality hybrid imaging detecting prostate cancer, real- time speech translation and digital cities encompass RAISA technologies and is the ‘evidence that dramatic change is all around us’ (Schwab 2016 p.8). These innovations are possible due to digital technologies that resulted from the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’, which ‘is comprised of new technologies that are said to ‘fuse the physical, digital and biological worlds, impacting all disciplines, economies and industries’ (Marr 2016, p.1).

There are concerns surrounding this, such as the loss of jobs for humans. For example, Chatbots enable predictive customer service, removing the need for employees to manually execute certain tasks. However, recent study found that digital technologies including AI actually created, 80,000 new jobs across a population similar to the UK (McKinsey 2017).

Furthermore, Industry experts suggest that RAISA applications could contribute up to 75% of revenue for some sectors of the market. According to (Preston 2015) countless companies will not succeed and the more technologically astute companies will emerge. For the PS, RASIA adoption is becoming of great importance. In the most recent edition of the Industrial Strategy, the HMRC place AI & data at the forefront of their strategy to be the industry of the future. The strategy highlighted how the Government will invest £406m in digital, technical and maths education and introduce a national re-training scheme to re-skill people (HMRC 2018). IT has been instrumental in the development of RAISA. The resources and capabilities aligned to IT seem to somewhat mimic that of RAISA (Chen et al 2015 Suzuki et al 2017); however, as RAISA presents a set of assets that differ from IT, both the complimentary and distinctive resources and capabilities must be examined to allow for integration and alignment for RAISA to be fully utilised within the PS. Previous research has not examined this, leaving many questions and unexplored areas around how this adoption will work in practice. In order for the PS to be able to ‘seize’ the opportunities before them, mass adoption must occur (Schwab 2016) – but to ensure success, there are barriers that need to be understood.

Hence, this study explores the capabilities and resources needed for the Public Sector to successfully adopt and utilise RAISA technologies.

Method

This study is adopting a Grounded Theory research method – normally used by post-positivist studies that aim to develop a theory (Annells 1997).

The author has decided to use semi-structured interviews as this format can include both structured and unstructured questions allowing the author to ask purposeful questions (Saunder et al 2016). Semi-structured interviews enable flexibility in questioning and employ theoretical sampling –exploring in depth certain aspects and adjusting interview guide as the data collection progresses (Corbin and Strauss 1990).

Interviews were carried out via Skype due to convenience, affordability and ability to increase sample by removing the issue of distance, which face to face interviews could cause (Iacono et al. 2016).

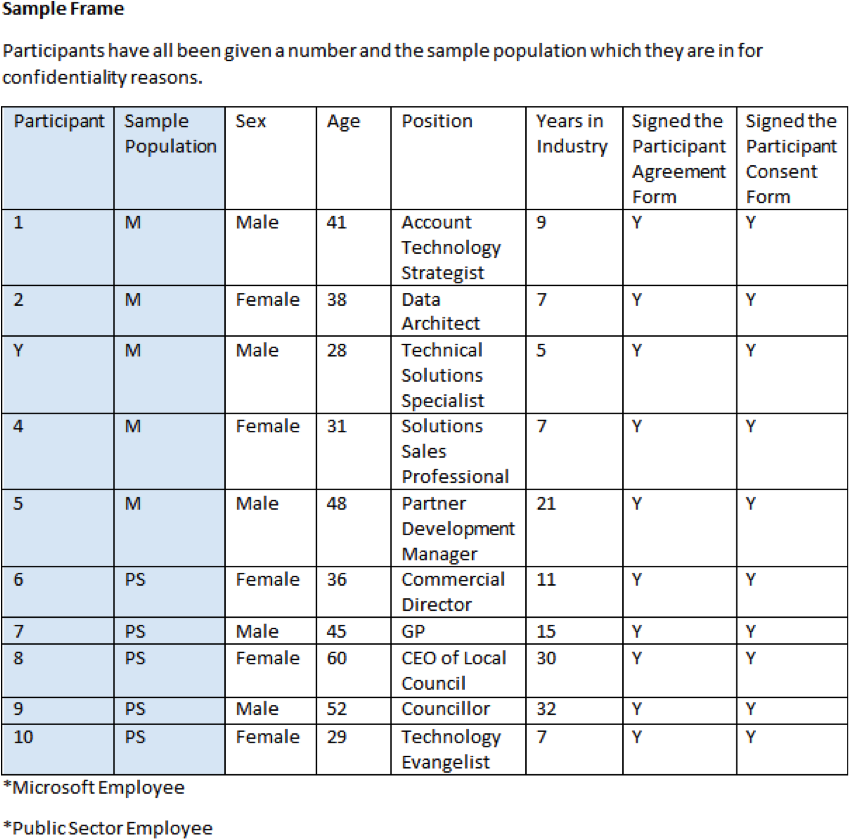

This study adopted the cross-sectional approach due to time constraints. This approach is less time-consuming than longitudinal and will allow the author to discover variations (Bryan and Bell 2015) which is fits the research method, Grounded Theory, by allowing the author to catch all applicable information as it appears, and identifying patterns and variations. This is crucial to successfully exploring a phenomenon (Corbin and Strauss 1990). See profile of the interviewees/participants below.

Findings: RAISA on the Public Sector Express

Hercule Poirot – the detective on the Orient Express. In this case, Poirot is the author. Poirot boards the Orient Express among strangers, but observes some peculiar events, which gives him the impression that these ‘strangers’ may know each other after all. He finds himself investigating the death of Ratchett (who kidnapped and killed Daisy Armstrong in exchange for money), who is murdered on the train. Evidence leads Poirot to the conclusion that all members on the train were involved with the death of Ratchett, and that all 12 passengers had links with the Daisy Armstrong case.

In place of a ‘murder’ we have RAISA stakeholders: Microsoft and PS employees. The ‘strangers’ knew which train they were getting and which seat they would be sat in but were not aware of the relationships between them.

RAISA is adopted with the same approach. It becomes apparent, that in both the film and in RAISA on the Orient Express the key theme is ‘relationship’. The capabilities and resources needed for the PS to utilise and leverage RAISA within the PS are both distinctive from and similar to those of IT. Each resource and capability may seem like the strangers on the train to outside individuals, but they are all related by the concept of ‘relationship’, which effects every element and ultimately achieves the outcome.

RAISA on the PS Express: (Image used, Post 2017, Authors Own Creation made in Photoshop, 2018)

Banking on the go: investigating reasons for use and impact of age

by Ellie Barker

Background

The technological environment is forever changing, especially in relation to accessibility. As a result, technological advancements have attracted new users throughout all generation classifications. ‘Banking on the go’ illustrates the increasing availability of accessing mobile banking services whilst on the move and away from physical banking institutions.

Adoption of mobile technology has reached 4.77 billion consumers globally and around 68% of consumers in the UK (Statista 2017). The mobile app market accounts for approximately 44 million UK users (Statista 2017). Mobile apps represent a unique business industry specialising in production and maintenance of mobile app product and services. Input, however, comes from other sector and industry players. Heading towards post-Brexit, financial services need to provide far more interesting customer solutions (Severn 2016). Technological elements are, today, part of this immersive and engaging service solution. For financial services in the UK, firms are required to provide threshold services and engage customers with commonly used touchpoints. Although banks are increasingly providing customers with mobile apps, consumers’ readiness and adoption levels vary (Bolton 2017). Therefore, understanding mobile app adoption is relevant in society today due to the convenient and useful features it can provide consumers, such as controlling finances instantly.

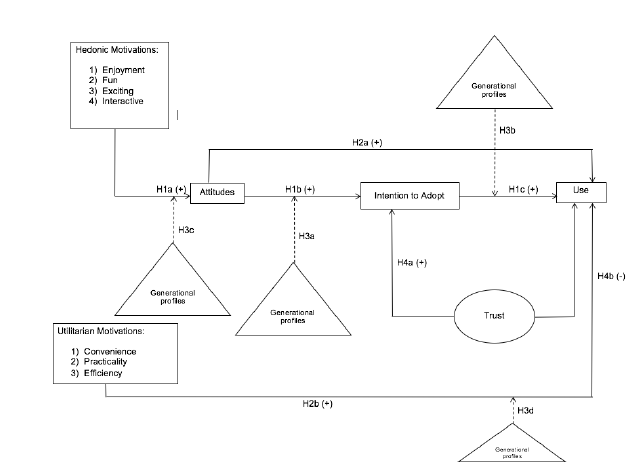

Literature on e-banking and mobile banking adoption is existing and well developed already, although some factors are still to be considered. Hedonic motivations and various constructs which stimulate both adoption and use of mobile banking have not been discussed in detail. Hedonic motivations include factors such as enjoyment of the online service and the technological design. Utilitarian motivations such as convenience, practicality and efficiency have also been ignored. This research project will focus on mobile technology, specifically the mobile banking industry and mobile banking apps. The research will investigate the adoption of mobile banking by assessing the relationships between mobile technology-specific factors and their effects on Generation Z, Millennials, Generation X and Baby Boomers. The aim of this project is to clearly examine the motivations and technology-specific factors of mobile banking adoption.

Despite impressive adoption figures worldwide many consumers remain unwilling to adopt mobile technology or the benefits of mobile banking. Around 19% of people are accessing their bank on a daily basis through one of three channels; mobile app, physical location or website access via a desktop (Bolton 2017). Previous research looked into task-fit and usefulness of mobile banking as triggering or preventing adoption. However, studies on hedonic motivations are fragmented and do not capture values of mobile technology applications (Bolat 2015). Technology-specific factors are currently not recognised throughout the mobile technology industry; therefore, consumers continue to refrain from adopting mobile banking and mobile banking apps. Academics tend to treat mobile app settings similarly to those of electronic service settings. There are qualitative in nature studies but the outcome of these have not been input for quantitative studies, which this study intends to address.

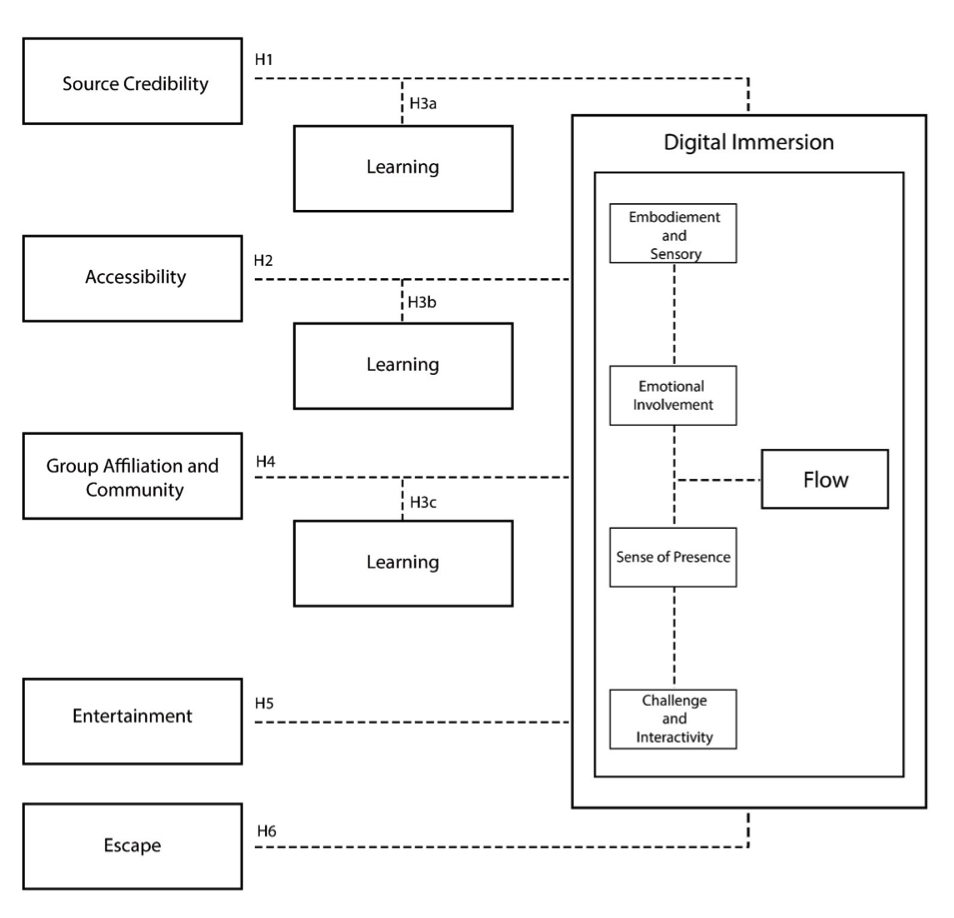

This research investigates mobile technology alongside how motivations and generational differences impact adoption of mobile banking services. The model below was tested.

Approach

A quantitative research approach was used in order to evaluate why users adopt mobile banking services, and to what extent motivations and generational differences impact their intention and actual use. A quantitate survey was generated on Qualtrics which was later distributed throughout various online platforms, such as Facebook, LinkedIn, WhatsApp and E-mail. The survey was used to measure user profiles, motivations and feelings towards mobile banking services.

Findings

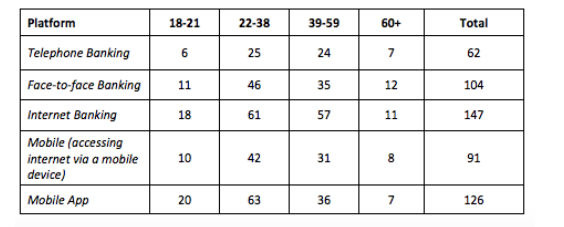

The survey received 213 responses with 31 responses missing. Hence, 182 responses are used for further analysis. Table 3 shows the majority of the sample, 40.88%, were aged 22-38 (Millennials) followed by 38.12% of the sample who were aged 39-59 (Generation X). A lower amount of responses was recorded from Generation Z and Baby Boomers. Further testing of the impact that generation gap, as a control variable (moderating factor).

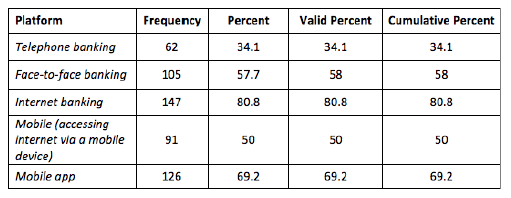

The majority of respondents take part in internet banking, mobile app banking and face-to-face banking. Interestingly, although traditional methods of banking, face-to-face and telephone are used, more and more technology-enabled banking services are in use (238 mentions across the same with Internet banking being used by almost 81% of respondents). It is also surprising to see the uptake of mobile apps (almost 70% of respondents are using mobile apps).

Interestingly, across the younger generational group (18-21 and 22- 38) m-banking is one of the most popular platforms versus the older generational group (39-59) who prefer internet banking and finally 60+ opting for face-to-face approach. This light touch analysis already demonstrates differences in generational profiles.

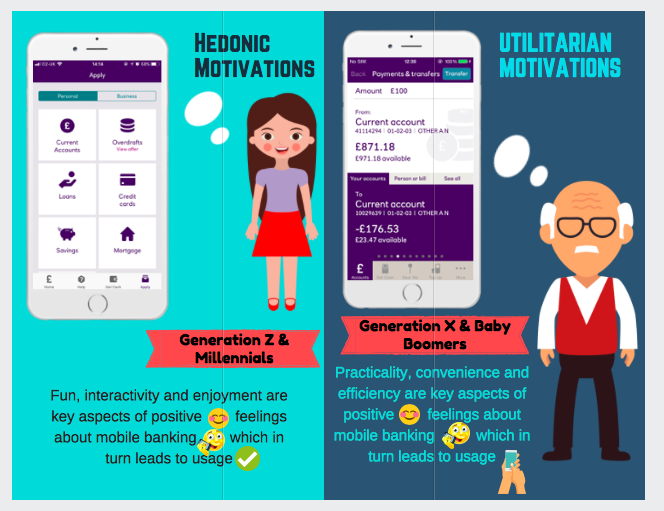

The findings supported most of the given hypotheses, suggesting that varying motivations and generational differences do influence adoption and use of mobile banking. Moreover, research found that younger generations are concerned with hedonic features, whereas older generations are focused on utilitarian features. Further research is required for expansion on generational profile motivations together with research on additional factors combined with the proposed motivations of this study.

H3A, H3B, H3C and H3D tested the impact of generational profiles on relationships surrounding attitudes, adoption, use and motivations towards m-banking services. H3A was rejected and H3B and H3D were only partially accepted as they presented insignificant results. The relationship between attitudes and adoption of m-banking had the lowest impact from generational profile. From this it is clear age difference does not have an impact on the relationship between attitudes towards m-banking and adoption of m-banking. This result contradicts the study of Foon and Fah (2011) which suggests age acts as a major influence on ITA m-banking. Nevertheless, results show generational profile has a slight impact on the relationship between adoption and use of m-banking, suggesting age is a determinant of continued m-banking use which is in line with part of Foon and Fah (2011) study which suggests younger generations who acquire technology experience are more likely to use m-banking services and apps than older generations. Results show generational profile also has an impact on relationships between UM and use of m-banking, suggesting UM, such as convenience, practicality and efficiency are more of a concern for older generations when using m-banking services compared to younger generations. This supports the study of Munoz-Leiva et al (2017) suggesting the key advantage of m-banking is the ability to manage finances any time in any location, proving a thoroughly convenient tool (Jun and Palacios 2016).

Furthermore, the research is in line with the study of Surendran (2012) which suggests PU and PEU are key determinants of adoption and use, especially amongst older generations. Additionally, mobility and portability have been proved the most valued features of m-banking services (Cruz et al 2010; Liang et al 2007), supporting the requirement of convenience for Generation X and Baby Boomers. New research findings suggest that generational profile has the strongest impact on the relationships between HM and attitudes towards m-banking. Results show 49.5% of variance in attitudes towards m-banking are explained by hedonic motivations when age is the moderating factor. This is substantial and suggests younger generations are predominantly concerned with HM, such as enjoyment, excitement and interaction, which determines their overall attitude towards m-banking services. This supports existing research from academics, as attitude is deemed a key determinant of technology acceptance (Chuttur 2009). Additionally, the study of Hew et al (2015) suggests consumers are more inclined to use m-banking services and apps if they are user-friendly with interactive features, which in turn develop positive attitudes and a customisable experience (Chaffey 2017).

Remaining hypotheses (H1A, H1B, H1C, H2A, H2B, H4A, H4B) tested the link between attitudes, adoption, use and trust towards m-banking, as well as differences in motivations. Firstly, results show that 81.7% of variance in use of m-banking is explained by positive attitudes towards m-banking. This is significant and financial institutions should implement trials or extensive marketing to encourage positive attitudes which should support uptake and use. Furthermore, 67.9% of variance in ITA m-banking is explained by positive attitudes which, as stated above, is in line with the study of Chuttur (2009) who found attitudes to be a key determinant of technology adoption. Positive adoption of m-banking has also shown a positive impact on use of m-banking which builds on the study of Oliveira et al (2014), focusing on adoption of technology and suggesting consumer performance can be explained through TTF.

New findings from the research also suggest HM have a slight positive impact on attitudes towards m-banking. This supports the study of Bolat (2015) on mobile technology distinctiveness, in which a new hedonic motive perspective derives from as emotional and creative value is developed from personalisation features and consumers also obtain social value from immediate access to communication channels. Additionally, 66.8% of variance in use is explained by a positive impact from UM which is extensive, hence financial institutions should install practical, convenient and efficient features within their m-banking services and apps to encourage continued use. This new finding supports the study of Ewing et al (2013) which suggests one of the highest-scoring features of consumer usage is integrated payments, therefore providing convenience for m-banking customers.

The last hypotheses were based on trust of m-banking services. Results show nearly 50% of variance in adoption of m-banking is explained by trust which is in line with the study of McNiesh (2015) which suggests consumers lack trust towards m-banking as they have to release personal information through a technological device. Additionally, results show nearly 60% of variance in discouraged use of m-banking is explained by distrust, building on the study of Lee (2009) which suggests consumers are discouraged from adopting and using technology if they obtain a level of PR, such as performance or financial.

The infographic below presents an infographic concluding the study. As shown, the younger generation, Generation Z and Millennials, are predominantly concerned with hedonic motivations in relation to adoption and use of m-banking services.

M-banking and impact of age Infographic creator: Ellie Barker

Hedonic motivations, including fun, interactivity and enjoyment, have been found to generate positive feelings amongst a younger demographic, which in turn encourages their attitude towards m-banking, but most importantly the use. In contrast, the older generation, Generation X and Baby Boomers, are concerned with hedonic motivations, including convenience, practicality and efficiency. These aspects have been found to generate positive feelings amongst the demographic, which in turn encourages use of m-banking as well as positive attitudes towards the service.

Digital Immersion: Is it what you thought it is?

Immersion is used outside of digital space as a term to measure the degree of involvement in a specific activity. Digital immersion is now a ubiquitous phenomenon that can be observed in all human activities starting with consumption of services and products as well as professional tasks.

Overall academic literature, in particular business and management literature, lacks understanding of digital immersion (DI) and as a result “immersion” is used interchangeably with “engagement” (Takatalo et al. 2010, p.27; Boyle et al. 2012; Bouvier et al. 2014; Parvinen et al. 2015). This project aims to examine what stimulates DI and how it causes behavioural changes in its users that keep them habitually absorbed.

The context of ‘streaming’ and e-sports presents opportunities to understand the DI in practice, enabling other digitally enabled businesses to borrow best practice techniques as well as create awareness of issues surrounding DI. Hence, e-sport, in particular Twitch.tv social community is chosen as a contextual setting to achieve the research aim.

Discussing Immersion

Immersion is used outside of digital space as a term to measure the degree of involvement in a specific activity (Denisova 2016). Brown and Cairns (2004 Cited in Denisova 2016) described immersion as a deeper state of engrossment, eventually leading to total immersion. This second definition highlights that immersion is more than a feeling, but a state of mind. In light of this Schettino (2015) explored 5 areas of immersion; embodiment/sensory immersion, emotional involvement, sense of presence, challenge/Interactivity and flow (deep focus).

DI and digital addiction are closely related. Ali (2016) described digital addiction as the “obsessive and excessive use of digital media which could be associated with negative life experiences such as distraction, anxiety and preoccupation”. Ali (2016) also highlighted the evolution of digital space starting to merge with physical space. Addiction itself is associated with a negative persona, could it be that technology and digital space are simply becoming an extension of our natural reality? It is becoming easier to lose awareness of our physical surroundings and become preoccupied with digital space (Gregoire 2015). As a result, psychologists are pushing for warning labels on smartphones to warn users of overuse. Moreover, persuasion is used interchangeably with the DI term (Denisova 2016). However, two terms are interlinked but still distinct concepts. Persuasion is about changing behaviour and attitudes (De la Hera Conde-Pumpido 2017). Immersion is a step and a collection of effects that all together can lead to persuasion. This essentially highlights that persuasion could be the outcome of immersion.

Immersion is an experience, it is a valued factor that players are subject to when interacting with games. This factor essentially provides the cognitive sense of “being in the game”, which results in the deep engrossment of players that leads them to direct all their thought and attention into the game, as opposed to their real-world surroundings (Brown and Cairns 2004 cited in Denisova 2016). Whilst in this state of total immersion, players lose track of time and forget about everyday concerns (Denisova 2016).

The following sections will look to explore the five areas of immersion proposed by Schettino (2015) in relation to streaming to determine if the platform is indeed immersive, not simply interactive.

Embodiment and Sensory

Krishna and Schwarz (2014) explored sensory marketing and embodiment, they defined this focus as “marketing that engages consumers senses and affects their perception, judgement and behaviour.” Kenderdine (2007 cited in Schettino 2015, p409) defined embodiment as “the experience of the world in all senses of the body”. It is also argued that tools, such as computers facilitate the means to perform actions that would otherwise not be possible. In doing that computers are therefore an extension of one’s body (O’Connor 2016).This is further elaborated to suggest that the mind is not limited by the restrictions of our biology, it is intrinsically rooted within our interaction with the world (O’Connor 2016).

Virtual gaming requires the use of mental and physical attributes, and with increased accessibility to technology the distance between virtual playing and real-world activity is becoming negligible (Sentuna and Kanbur 2016). The increased interaction with players provides a sense of acceptance in the digital environment and also stimulates further popularity (Sentuna and Kanbur 2016).

Embodiment is stimulation of the senses, however applying this theme in the digital context has led to the premise of “user defined reality”. To elaborate, the (digital) world in which the game takes place and the characters (in-game characters and avatars) are considered extensions of the biological self.

Emotional Involvement

Schettino (2015) viewed emotions as the feelings described by the participants of the study and their levels of enjoyment. One participant in particular expressed that “She felt the pleasure of being “immersed” in the soundscape” (Schettino 2015). This statement captures the link between emotion and immersion. Emotions can be viewed as concepts created by language in order for people to communicate moods and explain behaviours, this allows people to label and share their ‘emotional’ experiences (Latinjak et al. 2015).

Studies have been found to suggest that emotion plays an important role in ensuring that people engage with digital content and communities (Cohen 2014). Content that triggers emotional responses can lead to social sharing, this is the forging of connections in order to share emotional experience (Harber and Cohen 2005 cited in Cohen 2014). Games (digital or traditional) can trigger positive emotions such a happiness, in turn this contributes to the players (Streamer) or spectators (Viewers) overall enjoyment (Cohen 2014). Wang, Shen and Ritterfeld (2009) found that the most defining factor of enjoyment in gaming, is whether that game is considered fun or not. Games that are popular to play are therefore more likely to have a popular spectator activity (Jia et al. 2016).

Lee and Schoenstedt (2011) found that, similar to traditional sport, spectators are emotionally involved in the eSport and their favourite players. Viewers follow their favourite teams and are stimulated by their victories and losses. As for the players (or Streamers) the competitive nature is a vital emotive factor, it is important to demonstrate their skills over others and win (Lee and Schoenstedt 2011).

Sense of Presence

Schettino (2015) found a pattern that participants felt as though they had physically travelled to the destination of the soundscape, even though in reality it was an illusion created by the sounds in the study. In another study, Brown and Cairns (2004) identified three levels of immersion: Engagement, the first level of immersion. This captured the need for the gamer to invest time, effort and attention into the gaming experience: Engrossment, the second level of immersion. In this the controls become natural and the gamers emotions were intertwined with the unfolding of the game; Total Immersion, the final stage of immersion. In this the gamers described a sense of presence, reality faded away and the game was the only thing that existed. Brown and Cairns (2004) described this notion as “When you stop thinking about the fact that you’re playing a computer game and your just in a computer.” These arguments demonstrate an interesting element whereby an immersive experience transcends the boundaries of what the mind knows to be possible, and instead defines its own reality.

Challenge and Interactivity

The challenge element is a crucial part of the gaming experience and is one of the more appreciated factors of players, it keeps them interested and returning (Denisova 2016). eSports adds a new dimension to gaming, as it puts players against each other in a competitive environment whereby their “skills” and “talent” are determinants for their success. The challenge element is altered by ranking systems that are put in place to ensure that the challenge remains fair and provides a sense of achievement for each individual player (Hamari and Sjoblom 2016).

In this point, Streamers are immersed in the challenge and compete to demonstrate their skills to an audience. Viewers are demonstrating interaction with this competitive play similar to how traditional sport appeals to “psychological and social drives such as excitement, social interaction, competition, achievement, diversion/escape, knowledge application, identification with sport and fantasy” (Lee and Schoenstedt 2011). The nature of Twitch.TV’s chat application satisfies the need for social bonding and encourages viewers to chat and interact with each other and the Streamer.

Flow

Schettino (2015) primarily focused on the level of focus that the participants exhibited, in the sense that they were engaged and exploring the different elements of the room in the study as if it was real and the only thing that mattered. The participants lost track of time and had to be asked to move on because they were so ‘focused’ or immersed in the experience. Similarly, Csikszentmihalyi (1975) described flow as the process of optimal experience. People become so absorbed in their activities that elements outside of this focus become screened out and irrelevant. Csikszentmihalyi (1990 cited in Jennett et al. 2008) went on to present eight elements of flow: Clear goals; high degree of concentration; a loss of the feeling of self-consciousness; distorted sense of time; direct and immediate feedback; balance between ability level and challenge; sense of personal control; intrinsically rewarding.

Brown and Cairns (2004) recognised that ‘Flow’ and ‘Immersion’ are closely related and that they both progress through degrees of engagement. Flow can be viewed as a measurement for the level of immersion that is being experienced. In other words, it describes the level of deep focus being felt by the individual as a result of the 4 other constructs: Embodiment and sensory; Emotional involvement; Sense of presence; and Challenge and interactivity.

Contextual Focus: Twitch.TV

Twitch.TV was founded in 2005 under the name “Justin.TV” (Cook 2014). It has since grown to become one of the leaders in peak internet traffic, accounting for 1.8% which is just behind Google and Netflix (Cook 2014). Twitch describes itself as

“… a community where millions of people and thousands of interests collide in a beautiful explosion of video games, pop culture and conversation. With chat built into every stream, you don’t just watch on Twitch, you’re part of the show… If you can imagine it, it’s probably live on Twitch right now” (Twitch.TV 2018).

Twitch.TV is a hub for ‘user generated content’. This is essentially anything that is produced and developed by its members. It also hosts eSports tournaments and provide coverage to eSporting events. The gaming focus is still a key element and core identity of Twitch.TV (Alexander 2018).

Twitch users are free to view streams (Viewers) or create their own (Streamers). This accessibility and freedom has provided the foundations for Streamers to express their love for games, demonstrate their skills and make a living from doing something they enjoy (Gerber 2017). This accessibility also creates a dynamic that blurs the definition of a consumer and producer of content, a viewer can aspire, learn and become a streamer if they so choose (Jenny et al. 2017). Furthermore, it is argued that having such a platform has only led to more followers and buzz around eSports and the commercialisation of gaming competitively (Casselman 2015).

Streaming Interactive Culture and Nature

Traditionally, mass communication models followed a unidirectional approach to the dissemination of information. Whereby the senders of information are separate to the receivers of information, who are passive and rely on the sender (Chung and Nah 2009). The ‘streaming’ environment does not fit that example and audiences are encouraged to be engaged and active.

Two-way communication theory captures the ability for a brand to have multidirectional communication with the public, stimulating true dialogue (Archer and Harrigan 2016). Streamers take the role of the brand and interact directly with their viewers to create an immersive environment that viewers are a part of. The common interest between the viewers of that particular ‘stream’ is the ‘Streamer’ and the content they provide. However, there is little research that can determine what elements of streaming cause or amplify DI.

This two-way communication between Streamers and Viewers creates an interactive culture. Interactivity is described as having two distinct dimensions: medium interactivity and human interactivity. Medium interactivity is referring to the communication between users and technology; human interactivity refers to interpersonal engagement between two or more users of technology that includes a communication channel (Chung and Nah 2009). Twitch.tv provides a platform that enables both medium and human interactivity through empowering users to contribute to content and connect with each other.

Streamer-Viewer Relationship

Opinion Leaders can be thought of as individuals that are in a position whereby they can influence the thoughts, attitudes and behaviours of other people within their scope (Nunes et al. 2018). Streamers can be thought of as digital opinion leaders as they use their platform to engage with an audience.

Two-Step Flow Theory

The Two-Step Flow Theory (Katz and Lazarsfeld cited in (Uzunoglu and Kip 2014) describes how people recognised as opinion leaders interpret information they receive through media channels and pass it on to others, and as a result, increase its influence. Bloggers are considered to be online opinion leaders (Uzunoglu and Kip 2014), and similar to bloggers, streamers have the knowledge, expertise and concealed influential power that keep their audiences engaged in their content.

The ease of creating content, publishing and sharing it with individuals with similar interests has become easier, and studies have proven that personal communication is more powerful at affecting attitudes of individuals compared to mass media (Uzunoglu and Kip 2014). Katz (1957) identified common characteristics and behaviours of opinion leaders and used them to define three dimensions: Personification of certain values (who one is); competence (what one knows); and strategic social location (whom one knows). The first dimension relates to the values and traits of opinion leaders. Competence captures the opinion leaders’ knowledge and expertise of the subject. Finally, social location refers to the size of their network, with particular emphasis on the number of individuals that value their leadership in the subject (Uzunoglu and Kip 2014). Twitch allows a ‘two-way communication’ between ‘Opinion Leaders’ and ‘Individuals’. The three dimensions proposed by Katz (1957) can be looked at further to identify several constructs that can be tested to identify to what extent, if at all, individuals feel contribute to their DI; SC; accessibility; entertainment.

Source Credibility

SC refers to the extent an individual is perceived to be a reliable, knowledgeable and trustworthy source for information (Weirzl et al. 2016). This is a key attribute of opinion leaders as shown in the Two-Step Flow Theory (Katz 1957) and also considered a fundamental predictor of consumer acceptance with regards to product attitude (Filieri et al. 2018). It would be acceptable to apply the same characteristics of SC that one would apply to a professional athlete. The level of skill, ranking, professionalism demonstrated by streamers on their streams would prove their credibility to their audience.

Zha et al (2018) studied SC within the context of social media. The definition of SC in this context replicated similar themes along the perceived trustworthiness, knowledge and believability of the individual publishing content. There was also a suggested link to reputation, whereby if a user was to perceive the information being given was from a perceived credible source, they would also consider them to be reputable and would consider the information being provided to be of a better fit to the intended need Zha et al (2018). Zha et al’s (2018) study refers to “focused immersion” or “focused attention” as interchangeable definitions for the same described user behaviour. That focused immersion (or focused attention) is likely to lead to increased effort and better understanding, heightened enjoyment, curiosity and control. This research suggests that SC has an impact on focused immersion, hence the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Source credibility has a positive impact on digital immersion

Accessibility

The term ‘accessibility’ has multiple definitions in this study. Accessibility can be defined from its dictionary definition as “the quality or characteristic of something that makes it possible to approach, enter, or use it”(Cambridge Dictionary 2018). Within the context of this study it has two definitions. It refers to the ease of obtaining the technology to view or to broadcast streams. However, it also has another meaning that was highlighted through the literature. Accessibility can also refer to the interchangeable status of a ‘Viewer’ and a ‘Streamer’. As a result, the following hypothesis has been proposed:

H2: Accessibility has a positive impact on digital immersion

Jenny et al (2017) refers to the blurred definition of a consumer and producer of content and identified that consumers can aspire, learn and become producers if they choose. This introduces the concept of learning, or self-improvement within DI. Technology has advanced to enable new forms of learning (Moore 2013). Moreover, live-streaming platforms have two key capabilities which have been found to improve learning: 1) real-time interaction between viewer and streamers (Bradley and Lomicka 2000) and 2) video-based instruction (Duffy 2008). Twitch.tv has been described as a unique platform, where gamers who want to share their experiences with the gaming community can with ease (Payne et al. 2017). Research has described it as a “virtual third place, in which informal communities emerge, socialise and participate” (Hamilton et al. 2014, p.1315). Payne et al. (2017) found that Twitch.tv can have a significant positive impact on learning performance of viewers. This introduces a moderating variable surrounding viewers motivation to learn from the streamer, whether that is streaming as a function (e.g. streaming equipment/set-up, conduct) or improving knowledge or skill within the content (e.g. eSports/game knowledge and skill. A third hypothesis is proposed:

H3a: Source credibility has more impact on digital immersion when viewers desire to learn from the stream.

H3b: Accessibility has more impact on digital immersion when viewers desire to learn from the stream.

H3c: Group Affiliation and Community has more impact on digital immersion when viewers desire to learn from the stream.

Viewer Motivations

Successful games have many common attributes, one that stands out is the ability to draw a person in. This results in the person losing themselves in the digital world of the game, a term that people often describe as immersion (Jennett et al. 2008). This section looks at motivations of spectators of sports and translates that to the context of eSports and Twitch.tv.

Jia et al (2016) found that spectators study or watch streams for entertainment, which included repeatedly watching playbacks. Many sports attract large crowds, and followings that result in commitment to season tickets or collectibles and wearables (Mehus 2005). The Sport Fan Motivation Scale (SFMS) is a tool that was designed to measure the motivations of sports fans (Wann et al. 1999). Out of the eight categories identified, the following are also shared with literature surrounding immersion and eSports: Escape; Entertainment; Group affiliation (Wann et al. 1999). Escape captures the feeling of temporary relief from the ‘real-world’ (Wann et al. 1999). Entertainment within games captivate the players attention and hold it for long periods as players attempt to master the complexities of playing and accomplish objectives (Moore 2013).. Group affiliation refers to the desire to be surrounded by other people, a mutual bond that provides a sense of belonging and shared experience (Wann et al. 1999).

H4: Group affiliation and community have a positive effect on digital immersion

H5: Viewers perceived entertainment of a stream/streamer has a positive effect on digital immersion

H6: Viewers desire to escape from reality has a positive effect on digital immersion

Conceptual Framework

Digital Immersion conceptual model

What did we do?

We conducted survey, in particular, an internet survey distribution method has been chosen. This allows respondents easy and quick access to the survey (Sue and Ritter 2016). Twitch.tv has said they are willing to share the posts on their student social media. The popularity of this social media could be vital in the development of voluminous credible responses. NUEL (National University Esports League) will also share the link to the survey on their social media. This highlights the flexibility of the online survey method, it can be accessible through multiple destinations and audiences in a cost effective manner (Sue and Ritter 2016). Compared to email, it also offers increased levels of anonymity should the respondent desire it. It is important to recognise that this type of survey can result in respondents abandoning, being distracted and forgetting to complete. In addition, the increased anonymity through this opt-in style results in limited information about respondents (Sue and Ritter 2016). The impacts of these disadvantages will be minimised through careful planning and careful survey construction, to ensure that all questions asked are easy to understand and have purposeful with regards to the research.

Results

Firstly, it is important to note that survey population was mainly male. This is typical of the eSports environment as it is predominately occupied by males (Hamari and Sjoblom 2016; Jenny et al. 2017). However, this could be considered a limiting to the generalisability of the study as results were predominately from the male position.

eSports and Twitch.TV have grown rapidly over the last decade surpassing some traditional sports, as well as generating mainstream interest and sponsorships (Jonasson and Thiborg 2010; Casselman 2015; Hamari and Sjoblom 2016). This study proposed a definition for DI and discussed how DI could be responsible for the growth and success of eSports. DI is defined as “the use of computer technology which stimulates deep mental and emotional involvement”.

The main portion of this study focussed on measuring the level of DI being felt in accordance with constructs prevalent throughout the literature. Out of the four hypotheses that were tested, only one was rejected. However, even the rejected hypothesis is a surprising result that also will be discussed.

The results showed that “Escape” is the most positively effecting single construct to effect DI. The feeling of temporary relief from the real world and “mind travel” is widespread throughout immersion literature (Wann et al. 1999; Schettino 2015). It therefore makes sense that escape is a valued element of DI. It also further demonstrates that reality can be determined by the individual, and digital environments that allow users to define their own reality are more immersive (Brown and Cairns 2004). This highlights an interesting phenomena, and applying what Brown and Cairns (2004) explained with playing computer games to this context it leads to the concept: “When you stop thinking about the fact you’re using a computer and your just in the computer”. Interestingly, this leads to the concept that content should allow users to forget about the real world and encourage their user defined reality.

The results showed GAC as the second most positively affecting construct to DI. Schettino (2015) identified five areas of immersion, GAC can be considered to effect or provoke reactions in all five of these areas (Jia et al. 2016; O’Connor 2016; Sentuna and Kanbur 2016; Jenny et al. 2017). Specifically the work on the SFMS tool completed by Wann et al. (1999) shows links between the five areas of immersion and the and the eight categories of the SFMS. It could be argued that sharing the experience with others leads to further immersion as the inclusion of a community provides users with a feeling of acceptance and validation of their digital reality (Jenny et al. 2017). Twitch.TV allows people to engage with the Streamer and all the other viewers of that stream. This means that there are vast amounts of people with similar interests all engaging in social interaction creating a community. Regular viewers that engage with the chat systems are also very much part of the Streamer brand, recognised by the Streamer and other members of the community (Archer and Harrigan 2016).

The results showed that the introduction of Learning as a moderator variable to GAC had to strongest overall relationship with DI. Payne et al. (2017) described Twitch.TV as a virtual third place which has a significant positive effect on the learning, socialising and participation of its audience. Immersion and GAC both express the synergy of interaction with people, places and things (Hamilton et al. 2014; Schettino 2015; Jenny et al. 2017), therefore it is logical that content that stimulates and provokes self-improvement leads to deeper focus and DI. Learning was also looked at as an independent variable and the results showed that there was a significant strong relationship with DI. Due to two of the original hypotheses being determine as unreliable via Cronbach Alpha, learning was only considered with GAC. This will be further discussed in the limitations section. However, further research should explore how Learning contributes to other constructs, especially considering its proven direct relationship with DI.

Interestingly, and contradictory to literature, Entertainment (H4) was rejected. It was found to be insignificant and have no relationship with DI at all. Research surrounding sports consumption motivation (Wann et al. 1999; Jia et al. 2016) and immersion literature (Schettino 2015; Denisova 2016) expresses the requirement of “entertainment” in order to motivate or experience immersion. It could be argued that people are immersed in their everyday “physical” lives, and that day to day behaviour is not always entertaining. The assumption could be made that digital environments when viewed as an extension of the biological self (Brown and Cairns 2004; O’Connor 2016), are receptive to the same factors that influence immersion in the physical world. This would need to be researched further to clarify how closely people link their digital world with their physical world and whether there is indeed a separation at all.

The study proved the existence of DI within the environments of eSports and Twitch.TV. Figure 4.5 shows the results from the testing of DI through questions generated as a result of the literature surrounding immersion conducted by Schettino (2015) and applying that to the digital context. Majority of respondents feel they “somewhat agree” or “strongly agree” with these statements. The statements cover: embodiment/sensory immersion, emotional involvement, sense of presence, challenge/Interactivity. Future studies could look to determine the level of Focus being felt as a result of the level of agreement that users feel with each of the other constructs.

At the heart of digital immersion is community: The more that individual is experiencing community and feels part of that community, the more likely they are to be immersed in the digital environment. Contrary to existing research on online influencing we found to support to demonstrate impact streamers (aka influencers) have on digital immersion in the context of e-sports. Moreover, entertainment within content is also irrelevant to the digital immersion. Once again contrary to existing research. Finally, content that allows users to escape from reality and forget about real world problems, and learning in combination with community factors found to have strong and positive impact on digital immersion. Findings of this research have implications beyond its contextual focus, e-Sports. Businesses can utilise learning, escape and community effect to improve online presence and stimulate much more meaningful engagement with a digital content.

New additions to DigitalMe collection are …

New additions to DigitalMe collection are contestants for this year’s BU Research Photography competition. This year Charlie Simmons and Elizabeth Falkowska are taking part in the research photography competition.

Charlie’s work is digital tethering and in particular understanding Digital Immersion. Charlie is studying digital immersion within the Streaming and E-Sports context.

Elizabeth’s work is about challenges the advertising industry is facing due to emergence and adoption of RAISA (Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, Service Automation).

Vote for their entries via: https://www1.bournemouth.ac.uk/research-photography-competition

More about these studies you will be able to hear at the Digital Me Exhibition: Chapter II, on 16th June at Bournemouth University.

Slacktivism to Activism conversion is possible and leading to success

Original content was published via LinkedIn:

Launched at the red carpet events the Time’s Up movement is gradually moving it audiences towards discussing further the issues of gender inequality, abuse of power and sexual harassment in workplaces and industries. It is not about awareness anymore but about taking actions, hearing stories of others and supporting victims.

From the Time’s Up campaign example we see that social media campaigns are leading to more than just slacktivist behaviour. Society and audiences are listening and acting on information; they express empathy and they learn to be cautious. In the past two years my research colleague @FreyaSamuelson-Cramp and I have been looking into issues around outcomes achieved by social media marketing when it comes to promoting and engaging audiences and society with social causes, i.e. child abuse, poverty, immigration etc. Over the course of these two years we conducted empirical research into slacktivist behaviour and of course we have interpreted and followed through results achieved by famous social marketing campaigns such as IceBucketChallenge and KONY2012. In most of these cases we have seen amazing results in terms of awareness. Our study does show that slacktivists are engaging with the online social marketing campaign due to participatory and solidarity culture of social media. Psychological and emotional motives are strongly utilised by most social marketing campaigns, hence, they do achieve number of likes, shares and reshares – activity metrics of social media engagement. However, most of these campaigns, just like any social media content, are eventually lost in timelines of content, forgotten and dusted. What is different about Time’s Up? Below are some headings that I believe make Time’s Up a truly successful and different social media campaign.

STORY

Time’s Up movement created from the #MeToo campaign brings to light stories of sexual harassment in workplaces, entertainment industry and overall gender inequality issues where males are abusing own rights and power to undermine, disrespect and take advantage of women. The story of Men Power, and gender inequality (or should I say, Women Powerlessness) is documented in fairytales such as Cinderella (only prince can make cinderella a princess), Red Riding Hood (only the hunter could save the poor girl and her granny) is accompanying young children, leading up to embedded into upbringing differences in girls and boys. Today, however, stories are changing with Elsa relying on her sister to rule her land and Moana being the only person to save her people and in fact give back a demigod abilities to ‘powerful’ Mawi. And quite frankly these stories are not about battle of powers but the partnership of genders. #MeToo campaign, in light of these new stories, is not about females or males but about a suffer that abuse of power creates. This story united people, families, celebrities and their fans. Solidarity, community and emotions are three components that were critical stimuli to make #MeToo campaign a relatable story.

INTEGRATED MARKETING COMMUNICATIONS

Time’s Up movement is a continuous campaign that is reactive and carefully planned at the same time. However, its success is hugely depends on utilising omni-channel communication with events marketing at the heart. Major entertainment events such as Golden Globes, BAFTAs, Grammys are platform to talk to all people across the world using celebrities are transmitters of the message. This time, however, victims themselves play a role in communicating their messages and having a community of supporters by their side. The show embeds solidarity and partnership – this makes a positive attitude and support unavoidable. Watch my favourite speech by Janelle Monáe during Grammys: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DjqFGS5CwFA

Powerful, is not it? So, I can watch this speech over and over and share, reshare and comment because of social media channels like YouTube, Facebook, Twitter etc. TV channels, magazine covers, bloggers, any social media user have now shared their opinions and created own content to demonstrate solidarity and support. Bundle of channels and, hence, webs of conversations enable the Time’s Up to bring in financially and capabilities viable and critical partners (i.e. volunteer lawyers) together to help victims of sexual harassment and deliver a justice. Content and ubiquitous conversation enable victims to feel supported and speak out without feeling ashamed and hope to be supported.

It is not ends on communication and promotion only, we see changes in products and services – the whole marketing industry is reacting to #MeToo story with wearable gadgets being introduced to help victims in the incidents of attacks.

Overall, it is because of one single story and consistent and coherent multichannel transmission of the story, Time’s up, through crowdfunding vis-a-vis likes and shares, is building an army of supporters and people who truly can make difference to victims’ lives and build in policies and regulations, and change attitudes.

AUDIENCE JOURNEY MAPPING

Time’s up through awareness and move to interest and education is now slowly taking its audiences to stage of action and meaningdul engagement. This campaign is not about one reaction but Time’s Up aims to achieve a gradual combination of emotional and behavioural changes. With the global events at heart, the campaign is bringing in to spotlight the Story. However, behind the scene it enables others to conduct further research and form own opinion vis-a-vis social media conversations and follow-up media coverage. Now, gradually we see key stakeholders being involved in making visible and actionable changes that are to affect all of us via policies and cultural value shifts. This is what drastically differentiates Time’s Up from other social marketing campaigns. Here we see gradual journey, that all of us within the audience, conduct: from Awareness stage to Interest, Desire and now Action. Integrated marketing communications and careful mapping of audiences’ behavioural journey enables that conversion of slacktivists into activists.

SOCIAL MEDIA LISTENING

Social media listening is important part of a marketing research. It is mostly used in pre-campaign phases to shape story and make it relevant, current (or timely), choose channels and personas. However, in my article about Universities marketing I did write that social media listening needs to be everyday job of today’s T-shaped marketers: social media listening is not just about research but it is part of content development and social media storytelling – sensing when to release next chapter of your story, who to be the hero of your chapter. Time’s Up is doing this quite well and quite frankly it is not channel or event related. For instance after Golden Globes, Grammys and BAFTA events could easily shift attention to different phase of audience journey (as per above). However, Time’s Up did listen and learnt that audience was not ready yet and education (interest, desire) phase was to be prolonged.

PERSONA ENGAGEMENT, NOT DEVELOPMENT, APPROACH!

Although the campaign is aimed at everyone, there is a key persona for the Time’s Up – a victim (past, present and future) of sexual harassment. This persona is not narrowly described by her/his social media networks and other touchpoints, demographic and lifestyle profiling; this persona is defined by his/her journey in relation to the Story (as per above). This is quite different to other nonprofit or for profit marketing campaigns. Time’s Up is becoming a gradual part of its personas’ journeys, hence the campaign is underpinned by engagement approach. For instance, we see now gradual changes in attitudes that make victims of sexual harassment to be open about their stories. Next, Time’s Up is aiming to build a strong and leading to actual results support ecosystem that will enable victims to ‘break the silence’ and come forward. Future personas or these to be educated, and hence not to ever be victims, are part of the journey through education and learning and reassurance that this topic is no longer a taboo subject.

We are still to observe and learn about the Time’s Up campaign. However, one thing is clear about this social marketing campaign, it places key characters at the heart of its story, listens to conversations and evaluates readiness of audiences to proceed to the next phases of customer journey. It clearly uses a nonconformist – slacktivist – activist conversion as a foundation for its phased but continuous communication.

Universities need to adapt commercial brands-led marketing practices of social media listening and user-generated storytelling

by Elvira Bolat

UK universities still need to come to terms with the fact that the whole sector is experiencing great changes triggered by marketisation of higher education (HE) sector. However, given the changes are impacting the sector with such a speedy pace, commercial brand and marketing communication practices need to be adopted immediately – to remain competitive. In times of Teaching Excellence Framework when each UK university is graded for its commitment to teaching quality and student service, we now admitted that students are consumers. However, we still may argue that consumption of higher education is still a different process where prosumption, co-creation of experiences and students’ active role within the consumption process are significant elements of the educational journey. This is not the point we have tried to make in our recently published paper at the Journal of Marketing Management. Instead, we are calling higher education institutions (HEIs) to adopt “market-driven business practices” and attempt “to listen to and leverage student-generated social media content” (Bolat and O’Sullivan, 2017). “However, the power of content creators needs to be left or shifted to students, whereas the role of HE marketers, educators and other stakeholders is in listening and engaging via students as brand personas, students who truly believe in a specific HEI brand but also are able to generate authentic stories and conversations with current and prospective students” (Bolat and O’Sullivan, 2017).

The paper itself is based around a social media artefact, ‘This Is Where I Study’ (TIWIS) Facebook page, created by students in the form of dialogues and content.

Oxford as Student Destination: TIWIS team’s field trip to Oxford, May 2015. Photographer: Mahmut Bolat

Extract from the paper adds:

“TIWIS is essentially a ‘social journalism’ artefact that caters for international students seeking to study in UK universities. TIWIS utilised the social media and marketing expertise of BU journalism and marketing staff and students to produce reportage that prospective foreign students can draw from… BU students worked with teams from other UK HEIs for content production. The BU journalism team was drawn from MA Multimedia Journalism students, with the marketing team drawn from MSc Marketing Management students. The ultimate intention of the TIWIS project was to create student-related and relevant content with the intention of stimulating continuous students’ conversations which would first benefit and improve experiences of international students studying in the UK and second enable the generation of student-generated data that can be analysed and underpin the UK HEIs’ marketing initiatives as well as other business decisions.” (Bolat and O’Sullivan, 2017).

We have adapted three-stage analysis of netnographic data related to engagement with TIWIS page and content and found that:

“students’ engagement with social media platforms such as Facebook is dynamic in nature. It comprises behavioural expressions (manifestations and actions such as likes and shares as well opinion comments) and individuals’ experiences (subjective in nature stories and comments of personal experiences and views). Hence, netnographic analysis allows capturing actual behaviours via longitudinal ‘big data’ sets and support HEIs in proactive branding. Analysis of social media data demonstrates the value of encouraging and making accessible authentic conversations in order to create student-centred content.” (Bolat and O’Sullivan, 2017).

Read full paper at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0267257X.2017.1328458?scroll=top&needAccess=true

Full reference: Bolat, E. and O’Sullivan, H., 2017. Radicalising the marketing of higher education: learning from student-generated social media data. Journal of Marketing Management, pp.1-22.

HENRYs paper is presented at the Academy of Marketing 2017 Conference

Gemma Kennedy has travelled to Hull this week to present results of exciting research on the role digital tech plays in the luxury consumption process of millennials. This project adopted innovative elements of netnographic research within focus group study. To communicate results of this research we have used original illustrations contributed to us by Lucy Turnbull, Arts University Bournemouth graduate.

Read full conference paper via https://digitalmebu.com/2017/07/06/let-us-present-henry-family/

Let us present HENRY family :-)

This exploratory study examined the influence that social media has on the consumption of luxury products. We all know that social media has created a different dimension of consumers in various categories of products and services, and for luxury products in particular. That being, the ‘aspirational consumer’, whose desires for luxury derive from content produced on social media. Often, despite their strong yearning for luxury goods, due to economic reasons, aspirational consumers are unable to frequently purchase luxury. Social media provides an avenue for aspirational consumers to conspicuously consume without the need to purchase, enabling them to use luxury brands to create value amongst themselves. Aspirational consumers are mostly found amongst HENRYs (high earners, not yet rich).

Would you consider yourself one of HENRYs?

Research into the consumption of luxury goods has frequently been studied through the prism of Veblen’s (1899) Theory of Conspicuous Consumption (Truong and McColl 2011). Studies around the influence of social media on conspicuous consumption are fragmented. The literature reviewed revealed there is a need for an in depth understanding of the influence that social media has on HENRYs consumers behaviour prior to purchase. A hybrid qualitative approach using online and face-to-face focus group data was utilised within this study to map a journey of HENRYs consumption behaviour. WhatsApp was used as a focus group facilitation tool and this in fact is considered as originality of this research as no published studies report on the use of messaging apps as the qualitative research tools.

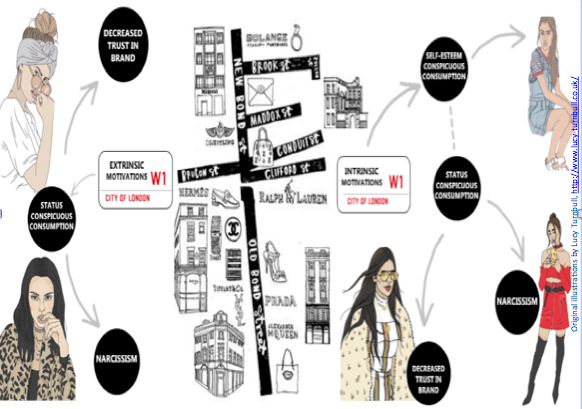

The map that we have developed as per illustration below reflects the role that social media has amongst the conspicuous consumption of luxury brands.

HENRYs’ map of conspicuous consumption, original illustrations by Lucy Turnbull

Findings highlight that status consumption is prevalent amongst HENRY consumers. The proliferation of social media usage further encourages HENRYs need for status goods. Social media provides individuals with an immediate environment for luxury conspicuous consumption. Social media influencers and user-generated media allow individuals to demonstrate their luxury status through the creation of social media content. HENRYs wish to emulate these behaviours from status influencers to produce their own social media content as evidence of their own luxury possessions. The reactions that derive from status posting satisfy their narcissist ambitions.

This research has been peer-reviewed and presented at the Academy of Marketing 2017 Conference in Hull, UK. The paper was praised by all attendees of the Consumer Behaviour track.

Reference for the conference paper: Kennedy, G. and Bolat, E., 2017. Meet the HENRYs: A hybrid focus group study of conspicuous luxury consumption in the social media context. In: Academy of Marketing 2017 3-6 July 2017 Hull, United Kingdom.

Full version of the conference paper can be found here: http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/29423/

Below, see presentation slides from the Conference.